'The Most Hated Guy On Wall Street': The Unspoken Story Around ...

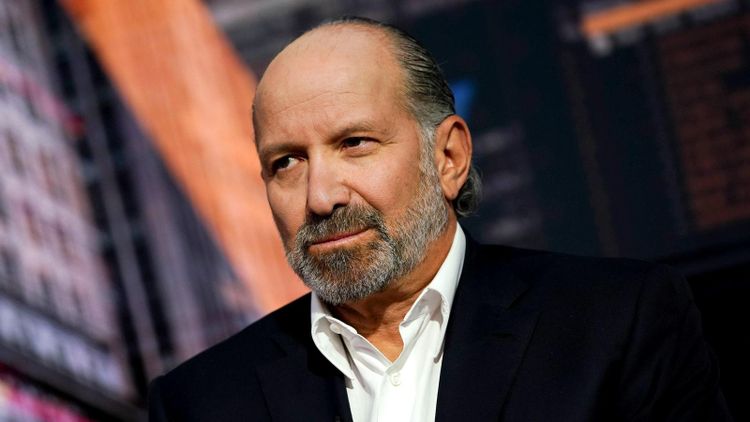

On the morning of July 27, Cantor Fitzgerald’s longtime CEO Howard Lutnick took the stage at Bitcoin 2024 in Nashville, Tennessee, where thousands of crypto fanatics had gathered to listen to royalty from the MAGA universe, including Vivek Ramaswamy, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and Donald Trump himself. During Lutnick’s 20-minute talk, the burly, balding 63-year-old made an impassioned defense of Tether, a cryptocurrency attached to the U.S. dollar, and announced the launch of an initial $2 billion financing business to provide leverage to Bitcoin investors. But before he began proselytizing, he retold a familiar story.

On September 11, 2001, he was dropping off his oldest son on his first day of kindergarten, when a plane struck the World Trade Center, where Cantor Fitzgerald’s headquarters sat on the 101st to 105th floors. All 658 of his employees in the building that morning were killed, including Lutnick’s brother Gary, his best friend Doug, 28 sets of brothers and one set of sisters. Describing the close-knit workplace, Lutnick recalled his hiring strategy: “We had an unusual model. We only wanted to work with people that we liked.” Out of tragedy came purpose. Lutnick promised to give 25% of the firm’s profits to families of the deceased for five years, eventually shelling out $180 million.

Twenty-three years later, Lutnick still sees himself as a model of patriotism and determination. Many others do, too. When Trump announced Lutnick’s nomination as commerce secretary on Truth Social on Tuesday, he did not focus on his business acumen or trade-policy knowledge. Instead, Trump mostly recounted the 9/11 events and described Lutnick as an “inspiration to the world” and “the embodiment of resilience in the face of unspeakable tragedy.”

It’s a true, and undoubtedly inspirational, story. But Lutnick has a darker side, which emerges in court documents and conversations with people who have done business with him. For years, they say, he and his firm have been pulling money from people—clients, investors, colleagues—making Lutnick, according to one former partner, “the most hated guy on Wall Street.” His multibillion-dollar empire–which includes two publicly traded companies and a privately held investment bank—is a tangle of self-dealing, with recordkeeping issues that date back decades and infighting that continues to the present day. “The whole firm is about f——— people,” says another former employee. “It’s about squeezing people.”

Lutnick runs his firm through a partnership, but there is no doubt who has the ultimate say. Now worth more than $1.5 billion, Lutnick pays himself like a king, cutting into partnership profits. “He could do what he wanted,” says a former partner. According to a lawsuit filed last year in federal court, Lutnick made employees take 10% to 20% of their pay in partnership units, which sounded nice but caused problems when the employees tried to get their money out. Agreements allegedly gave Lutnick sole authority to stiff former partners whom he believed violated broadly defined non-compete provisions. An estimated 40% did not end up with all their money after departing, according to the lawsuit, which says it was all part of a scheme to fool employees and enrich Lutnick. “He only pays if he wants to pay you,” says another former colleague. Lutnick’s companies have moved to dismiss the suit.

Through a spokesperson, Lutnick declined to be interviewed for this story. He does have defenders, who suggest some people just aren’t tough enough to handle him—or smart enough to read through the partnership agreements that one executive estimates run 700 pages. Even those who support Lutnick, however, aren’t eager to share their thoughts on the record. “People are very scared of him,” says a former colleague. “I witnessed this stuff first-hand. I witnessed the bullying. I witnessed the aggression.”

Combativeness might be just what Trump is seeking in his commerce secretary–especially if it’s combined with loyalty. In early 2021, when much of the business world was itching to move on from Trump, Lutnick remained by his side. Trump was just starting to form a media and technology company, with dreams of creating a Twitter knockoff, though the former president apparently did not want to put up much of his own money. Lutnick seemed like the perfect guy to provide the cash. After roughly 40 years in finance, he had experience taking advantage of all sorts of Wall Street trends, including the latest—special purpose acquisition companies—which injected liquidity into private companies, taking them public in the process.

Lutnick had a Zoom with two former Apprentice contestants who were helping Trump build the business. “Amazing call,” Trump’s team gushed in notes obtained by Forbes. “Howard says for us to drop other SPACs. He will fly down on March 30 to meet prez.”

Trump and Lutnick had known each other for years and shared plenty in common, both having made early fortunes in New York during the 1980s, one in real estate, the other on Wall Street. They operate similarly, too—flitting from one moneymaking scheme to the next, sometimes attracting the attention of authorities for issues involving fraud, poor recordkeeping and money laundering. Both tough guys, they share a taste for finer things—Lutnick once lived in a Trump Palace apartment, staffed with an English butler, before purchasing a 10,600-square-foot townhouse directly next door to Jeffrey Epstein. (A spokesperson says Lutnick “never had any association with Mr. Esptein.”)

Trump and Lutnick also have one key difference. The president-elect tends to avoid details—during his first term, aides learned to dumb down their presentations with bullet points. Lutnick, by contrast, obsesses over minutiae, having made a career slicing small profits from massive transactions, exploring virtually every nook and cranny on Wall Street—equities, bonds, swaps, futures, derivatives, cryptocurrencies and SPACs.

That difference became apparent during the discussions about Trump’s media business. Never the best at vetting people, Trump wound up getting financing from a smaller player, whom the Securities and Exchange Commission later accused of committing fraud as part of the deal. Lutnick, meanwhile, moved on, finding another company like Trump’s, Rumble, which had a MAGA-friendly knockoff of YouTube instead of Twitter. Through Cantor, he took it public in September 2022 via a SPAC and made a fortune, thanks to a favorable deal structure, even as mom-and-pop investors lost money. “If you’re not on Howard’s level,” says one former Cantor partner, “you’re just another piece of s—- in his way.”

Lutnick’s attention to detail is now on display in a new partnership with Trump, who tapped him to co-chair his transition team before nominating him as commerce secretary. While the president-elect focuses on his social-media account and headline-grabbing nominations, Lutnick burrows in on the lower-level appointees who actually carry out the government’s day-to-day work.

Cantor Fitzgerald interfaces all sorts of federal agencies and departments, raising obvious conflict-of-interest concerns. But while the Trump team considers people for agencies like the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which fined Lutnick’s firm $6 million for bad record keeping in 2022, it seems likely that Lutnick is just plowing ahead, without worrying too much about complaints from ethics watchdogs. “He only cares about himself,” says one former employee. “Trump is president for his own personal gain. Howard Lutnick runs his business in the same way. These guys are peas in a pod.”

The middle son of a college professor, Lutnick grew up on Long Island, showing an early knack for making money. As a kid, he bought new packs of baseball cards, then mixed them with old ones and sold the reassembled packs. Some would be jackpots, with five new cards; some would be duds, with just one. Other kids loved the surprise, but Lutnick got a thrill from certainty, knowing he could sell his reassembled packs for three times the cost of the new ones.

Life got tough as a teenager. Lutnick’s mother died when he was 16, his father when he was 18, leaving Lutnick and his older sister to care for their 15-year-old brother Gary. Howard Lutnick stayed in college at Haverford in Pennsylvania, hosting Gary from boarding school on the weekends. The elder brother graduated with an economics degree in 1983 before returning to New York and joining Cantor Fitzgerald, then helmed by its colorful founder, Bernie Cantor, who became a mentor. Cantor loved arbitrage and shifted from one thing to the next, always hunting for an advantage. He eventually found a niche as a broker in the multi-trillion-dollar Treasury market. Unglamorous work led to a glamorous lifestyle for Lutnick’s boss, who once stayed overnight in the White House as Bill Clinton’s guest.

Lutnick made a fast impression. Two years out of college, he was already trading for some of Cantor’s personal clients. “Bernie wouldn’t hear a bad word about the kid,” a former executive of the firm told Forbes nearly 30 years ago. “If you presented him with evidence that Howard crossed the line, he’d say, ‘Don’t worry. He’s young. He’ll learn.” In 1991, the year Lutnick turned 30, he took over day-to-day management of the firm.

Controversy followed. Lutnick surrounded himself with friends and family, including his younger brother Gary, who colleagues said sometimes jumped ahead of customers with bond orders, purchasing some and then quickly offloading them to the customer at a profit. Clearly illegal in the stock market, frontrunning might have been permissible in Treasury bonds, ethics notwithstanding. In 1994, the Securities and Exchange Commission fined Cantor Fitzgerald $100,000 for bad recordkeeping tied to risk-free investments at Treasury auctions. Three years later, the firm, without admitting or denying the findings, agreed to hand over $500,000 to settle charges that it assisted in fraud.

Even Bernie Cantor’s family eventually had trouble with Lutnick. Around the time Lutnick became CEO, he got Cantor to change the firm from a corporation to a partnership. In 1995, with his mentor’s health in decline, Lutnick teamed up with two other partners to try to buy out the Cantor family. The deal never happened, so in January 1996, Lutnick activated an incapacity committee that had been outlined in the partnership agreements. That five-member group voted to strip Cantor of control of the firm he founded, with three voting in favor and two abstaining. Cantor’s wife Iris, one of the abstaining votes, ended up in court. She came away with a pile of cash, no control and a burning distrust of Lutnick, whom she barred from visiting her husband’s cemetery.

Lutnick moved on, celebrating his 35th birthday at the Metropolitan Club in New York the weekend after Cantor died. In control of the firm, he stretched Cantor Fitzgerald far beyond its roots in Treasurys, diving more deeply into bonds, derivatives, swaps, futures, you name it. Revenues tripled from 1991 to almost $600 million in 1996. Looking to the future, he launched an electronic brokerage platform named eSpeed that year, a move that would help save the firm when tragedy struck.

Lutnick liked the high life. In the mid-1990s, he resided in what was then the tallest building on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Trump Palace. When he was not home, Lutnick could often be found at his office on the 105th floor of the World Trade Center. But then the unimaginable happened—a jetliner ripped through floors 93 through 99 at 8:46 a.m. on September 11, 2001.

Sympathy helped the business stay afloat. The electronic platform, eSpeed, upped its market share in the aftermath of 9/11, then squandered the gains when Lutnick introduced a new service that allowed bond buyers to jump in front of others by paying more than triple the standard rate. Customers fled, and eSpeed ultimately gave up on the idea. Lutnick kept wheeling and dealing, playing with the structure of his empire. Having taken eSpeed public in 1999, he merged it with other brokerage operations in 2008, naming the combined public company BGC Partners. The market expressed skepticism, applying what one investor termed the “Howard Lutnick discount.” Lutnick found a way around the problem, breaking eSpeed back out of BGC and selling it to Nasdaq OMX Group in 2013 for $750 million in cash, along with stock payouts over 15 years.

Creating some distance between his fortune and his reputation proved to be a wise move. Nasdaq shares took off, making the payouts increasingly valuable and lifting the eventual size of the deal above $2 billion, more than BGC was worth at the time of the transaction. To help manage everything, Lutnick hired a right-hand man named Anshu Jain, who had served as co-CEO of Deutsche Bank from 2012 to 2015, the years the German institution offered Trump $340 million of financing.

Lutnick also pushed into real estate, buying a handful of firms, then rolling them up into Newmark, which finished a spinoff from BGC in 2018. Newmark grew into a multibillion-dollar real estate service firm, helping with sales, loans, leases and property management. Among its clients: the Trump Organization, which hired Newmark to sell its D.C. hotel. In addition to the real estate business, Newmark also took a side asset in the spinoff—the right to BGC’s shares in Nasdaq, which paid out in December, providing a roughly $100 million annual income stream.

Such dealmaking takes brains, and even Lutnick’s enemies concede that he’s sharp. “Absolutely brilliant,” says one. “Very, very smart,” adds another. “I will say this,” chimes in a third, “Howard works hard and usually gets what he wants, one way or another.”

Just not always in ways that make everyone happy. In June 2021, Lutnick allegedly demanded that the compensation committee of Newmark’s board pay him a $50 million bonus, citing his work on the Nasdaq deal, which he struck four years before Newmark even became a public company. According to a lawsuit later filed by shareholders, the committee initially decided to push back consideration of the award. The chair of the committee, whose husband died on September 11, broke the news to Lutnick. The boss allegedly flexed his muscle, making his displeasure known, and the board evidently reconsidered. Lutnick ended up with a $20 million bonus in 2021 and a $10 million bonus for each of the next three years, adding up to $50 million—the same amount he allegedly requested.

The board, which Lutnick chairs, says the lawsuit has no merit and defended its move, suggesting the big bonus would help keep the boss engaged. It may have, for a few years. But Lutnick’s fourth and final payment is scheduled to land at the end of 2024. It’s great timing for Lutnick, who will likely leave his business about a month later to enter the president’s cabinet.

MORE FROM FORBESFollow me on Twitter or LinkedIn. Check out some of my other work here. Send me a secure tip.