In his own words: Limerick not just another town for Johnny Duhan

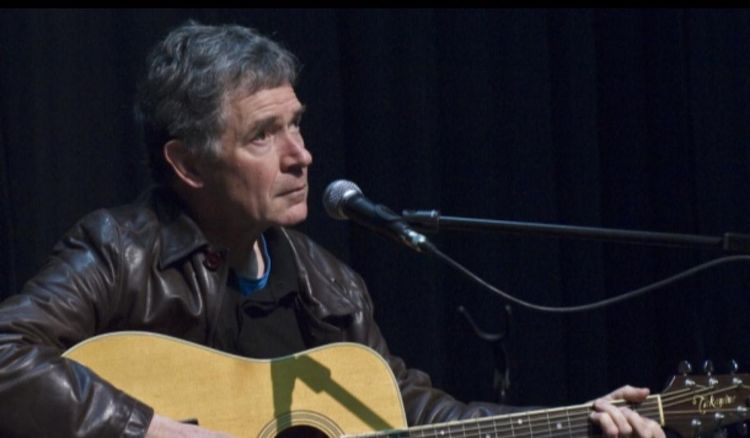

WHEN Alan English, the Limerick Leader editor, asked me to write this piece on reflections of growing up in Limerick, I didn’t have far to go to find a starting point, for my album Just Another Town is a hymn to the city I grew up in.

In fact, each of the 17 songs that make up the collection were achieved after deep meditation on memories of the hometown and on the family, friends and neighbours that I grew up among on Wolfe Tone Street.

The horn that features on the opening song Another Morning is an echo of the trumpet from neighbouring Sarsfield Army Barracks that used to wake my brothers and sisters and I when we were growing up. The songs that follow recapture the key experiences and influences that shaped my early life.

Old friendships are revisited, carnivals are brought back to colourful life, neighbourhood bars are evoked, chapel bells ring out, church choirs break into high register. Darker tones dealing with suicide, homelessness and depression are also expressed, for I wanted to paint an accurate and honest picture of the town, not create a sentimental pastiche of the place.

Some of my oldest, grittiest memories of Limerick centre on the Shannon and the harbour area around the docks, mainly because my father was a merchant sailor when I was young. Like the son of Ulysses, Telemachus, I gravitated to where the ships came in as a boy in high expectation of spotting my father among an adventurous crew. I imagined him then as a kind of conquistador.

READ MORE: ‘Thank you for the beautiful music’: Tributes paid to the late Johnny Duhan

My fantasies in this regard – which years later would colour many of my songs, including The Voyage – were fed on an early love of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (both tales ingested from the screen of the Lyric cinema on Glentworth Street way before I devoured them in print).

My mother once told me that when I was seven or eight I went missing from the street and was found in the docks chatting to sailors and stevedores. A devout Christian, my mother compared finding me among the nautical fraternity to Christ being found by his mother and father among the scribes and wise men in the Temple at Jerusalem when he went missing as a boy. I too was about my father’s work, learning the nuts and bolts of the trade I thought I was going to follow my father in.

Singing was an activity I picked up early from my father also. Renowned for breaking into ballads like Ramona and soldier songs like Keep Right On Til The End Of The Road in the public houses around the dock area and Wolfe Tone Street, my father often brought me along to Joe’s Bar on Henry Street, where his baritone was greatly appreciated.

The tone and substance of the songs I soaked up in those smoky establishments emerged years later in songs like Don’t Give Up Till It’s Over, There Is A Time, Let’s Just Have Another Drink, Stowaway, Two Minds, and Just Another Town. I have often admitted that the soundscape of Just Another Town came from the bars, dancehalls, homes, factories, schools, chapels and the very streets of our neighbourhood locality.

From a very early age, I was deeply affected by church music. When I was seven or eight I remember breaking into tears in St Joseph’s chapel on O’Connell Avenue while listening to the choir singing a Latin hymn during a Benediction service. Though I hadn’t a clue what they were singing about, the melody and timbre and high pitch tone of the voices pierced my heart like a harpoon and drew me into a musical whirlpool that I’m still immersed in.

One hymn that the local choirs sang in the vernacular, Hail Queen of Heaven, resonated for me because it alluded to the hazards of the oceans where my father plied his trade. Echoes of the church music that I absorbed back then emerged in songs like Mary and Benediction, and for me, they are an integral part of the mix of the collection.

A few years after I released the first edition of Just Another Town, I learned that Limerick’s most famous alderman Jim Kemmy had chosen the album as one of his favourite records during an interview on RTE radio with Pat Kenny. Soon after that, Jim started corresponding with me, sending me copies of a Limerick magazine he edited and contributed articles to, the Old Limerick Journal. One article he directed my focus to dealt with The Bells of Limerick, probably because he knew that the same bells that he wrote so affectionately about were a ubiquitous feature on the record. Given Jim’s staunch agnosticism, I was surprised that he waxed so lyrical on the charms of the chimes of Limerick churches, but he himself felt there was no contradiction in this.

As I entered my teens I developed a passionate relationship with our ‘wireless’ and the international popular music that emanated from it. I also started attending ceilis and “hops” and became aware of the vibrant musical scene that Limerick had to offer. I become fixated on names like the Brown Brothers, The Hockedys, Cha Haran, Tommy Drennan, Ger Cusack, The Empire Showband, Bill Whelan, Jim Whelan, Denis Allen, Jack Costelloe, Johnny Fean, Joe Healan, Guido De Vito, Joe O’Donnell, Fats Fallahee, to name just a few of the town’s popular musicians.

From the age of 15 I rubbed shoulders with many of these local legends in dancehalls, clubs and talent competitions.

Eventually, I joined Ger Tuohy’s group The Intentions (later Granny’s Intentions) and we formed the mad idea of aiming for the stars.

I have always found it ironic that, though I left Limerick in the mid-60s at 16 to pursue a career in popular music in Swinging London with Granny’s Intentions, it wasn’t until I returned to live in the west of Ireland after my rock adventures were over that I discovered that the real source of creativity for me resided back in the place of my genesis, Limerick city.

In the wide reading I immersed myself in while living in the country I came upon an explanation for my return in memory to the homeplace to get my bearings for the future in a phrase written by the French writer Pascal: “Wisdom returns us to youth”; and in another by Wordsworth: “The boy is father of the man”.

Basically what these writers taught me was that the source of true character is formed in youth; and though the growing man is prone to go off the rails and lose his way - and even lose his heart and soul at times - there remains open to us always a way to rediscover who we really are by touching base with our younger selves. Wasn’t it Christ himself who suggested that we must become like children to find our way to heaven? Since I left Limerick in my teens the city has been cast in a dark shade by the growth of sinister elements that have brought havoc and mayhem to the town and given the city on the whole a bad reputation. That period is now hopefully coming to an end, after the removal of certain poisonous behaviour from the streets.

Sinister influences will always impinge on modern city life. Limerick is little different to other cities in Ireland and elsewhere in this regard. Visually, every time I revisit Limerick now I’m conscious of just how picturesque the place looks as I drive across the Whistling bridge and look along the bright quaysides. While I was growing up, this part of the city had its back to the river and was overrun with delapidated sheds and warehouses, whereas now the pristine buildings along the waterfront face the the Shannon river, the greatest asset Limerick has – after the asset of the fine people that make up the city.