Stylish Charlie Hurley played like he was 'centre-stage at the ...

When England hosted Ireland in a World Cup qualifier at Wembley on May 6th, 1957, Charlie Hurley paid in at the gate. A promising centre-half with Millwall in the old Third Division South, he was reckoned by many to be on the verge of an international breakthrough, so he wanted to check out first-hand what the standard was like. An injury had forced him to turn down a call-up to the Irish squad two years earlier but, following a 5-1 defeat in London that afternoon, he was immediately brought in for the return match at Dalymount Park 11 days later.

“That made my father the happiest man in the world,” said Hurley in Sean Ryan’s ‘The Boys in Green’. “He always said I’d wear the green jersey. For four weeks from the time I was picked he never did a day’s work. He worked in Fords and the factory was full of Irish. He sat in a corner talking to them all about his son – and the fact that I had a good game gave him the two weeks after. He was king for a month.”

It’s not difficult to imagine the pride his father must have felt. The Hurleys had left their home in Devonshire Street exactly 20 years previously. Like thousands more Corkonians in the depressed 1930s, they sailed to England in search of a better life. Charlie Hurley wasn’t even one when they sailed from Penrose Quay. Now, a few months short of his 21st birthday, he was being invited back to bulwark the Irish defence in a game against the country where his family now made their home.

With fellow Corkonians Pat Saward (then of Aston Villa), and Noel Cantwell (West Ham) also in the starting XI, Hurley’s debut was auspicious. He completely obliterated the threat from legendary English centre-forward Tommy Taylor, who’d scored a hat-trick in the Wembley fixture. Afterwards, Liam Tuohy enthused that Ireland had discovered a “colossus who could grace any international team.” By the time Ireland gathered for an international again the following October, Hurley had moved to Sunderland for a fee of £20.000.

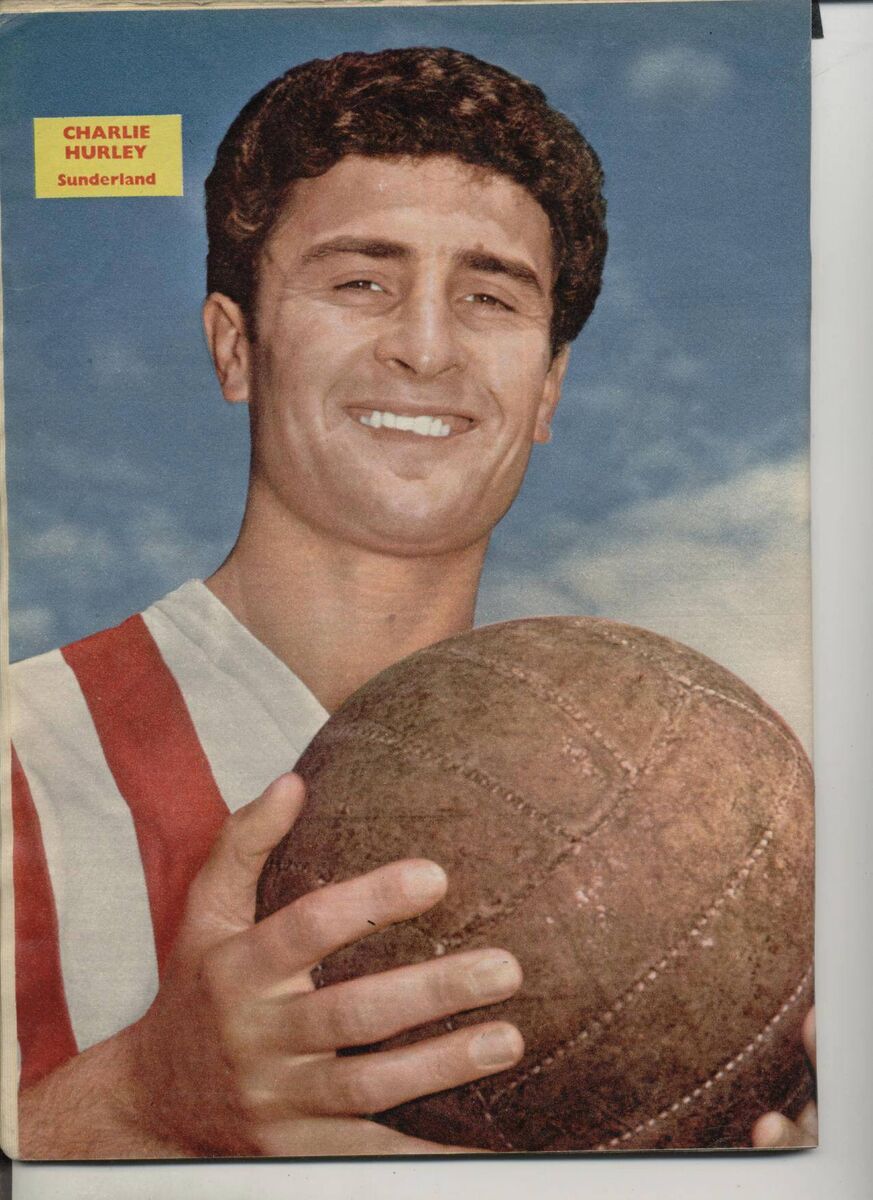

He stayed 12 years in the North-East, clocking up over 400 first-team starts during which he left an enduring legacy. Voted Sunderland’s “Player of the Twentieth Century”, the club training ground bears his name, and, in 1997, he was given the singular honour of laying a sod from Roker Park in the centre circle of their new home, The Stadium of Light.

“I was the first centre-half to go up for corners,” said Hurley. “Jack Charlton said he was, but he was lying.”

Every time Hurley strode forward into the opposing box for a corner kick, the Sunderland fans would hail his arrival with a chorus of “Charlie, Charlie, Charlie”. He repaid that faith with goals on 26 occasions. In the summer of 1999, he received an honourary degree from Sunderland University. After the ceremony, students born long after he retired queued up to get his autograph.

“Remember Charlie Hurley of Sunderland?” wrote Michael Parkinson. “He could play a bit. He used to give his supporters and team-mates palpitations by dribbling the ball out of the tightest situations. I saw him at Barnsley beat three attackers in his own penalty area and then float a perfect pass out of defence, but not before he first flicked the ball onto his head and down to his instep as if he was centre-stage at the London Palladium.”

Echo SportCharlie Hurley, Sunderland /CHARLIE HURLEY SUPPLEMENT 07 /CORK CITY V SUNDERLAND supplement 07Hurley could play with the ball at his feet but it was his bravery and physical presence that endeared him to the Sunderland fans. As a consequence of his parents’ emigration, his accent may have been more Cockney than Cork but his commitment to the Irish cause was also exemplary. For more than half his international appearances, he was captain, and for his last three caps, he even stepped into the breach as player-coach, a thankless job at a time when the squad was selected by a group of FAI blazers called “The Big Five”.

Hurley’s character was evident on and off the field. When Bohemians’ Willie Browne won his first cap against Austria in Vienna – playing his part in a well-deserved scoreless draw – his amateur status precluded him from receiving his match fee from the FAI in the dressing-room afterwards. Hurley noticed this and took immediate action. He organised a whip-round among the rest of the squad and the joke was that Browne ended up making more money than the professionals.

Sadly, injury prevented him from playing against Spain in the infamous 1965 play-off defeat in Paris. That was the closest the team had come to qualifying for a major tournament during Hurley’s era. He called time on his career at international level with typical unselfishness. Against Hungary in May, 1969, he took himself off at half-time and brought on the younger Frank O’Neill in a tactical reshuffle. A month later, Hurley left Sunderland for Bolton Wanderers and his stint as one of the most highly-rated defenders in England began to wind down.

After finishing his playing days at Bolton, he was appointed manager of Reading in June, 1972. With little resources, his five year tenure still had its moments. In 1976, he led Reading out of the old Fourth Division, the club’s first promotion in half a century. As the players celebrated on the field at Cambridge United, the travelling support chanted Hurley’s name until he emerged from the dressing-room and told them, “You’re the people we do it all for.” A year later, he was gone.

“I won very little as regards trophies as a player,” said Hurley. “In fact, I don’t think I won any. I got promotion with Sunderland – but we didn’t get a trophy because we were runners-up. I got a lot of caps. I was voted Ireland’s Footballer of the Year. I’ve been made Sunderland’s Player of the Century and I won the first Hall of Fame for Ireland’s internationals. But I won those things as an individual and I always wanted to win things with a team. That was my ambition.”

On one trip back to the city where he was born, Hurley was dismayed to find the house where he was born had been pulled down. He never tried to fake excess knowledge about Cork. But he retained enough of a connection with the place to return one time to receive the Cork Soccer Legends Award. At that function, he told the story of his international debut.

“When I told my father I was marking Tommy Taylor, he replied, ‘Don’t leave him breathe, boy. Stick to him like glue. Even if he goes to the loo, follow him’. I took Dad’s advice. I went everywhere with Taylor. Every turn he made I was there in front of him. When he stooped to tie his lace I stood over him. When he was being treated after a tackle, I smiled mischievously at him. I didn’t get to follow him to the loo but when the final whistle blew I noticed that he made a mad dash in that direction.”

A career encapsulated in an anecdote.

This is an abridged version of chapter that first appeared in Giants of Cork Sport.